Greater Yellowlegs

General Description

The Greater Yellowlegs is a mottled gray wading bird with long, bright yellow legs. It is similar in appearance to its smaller relative, the Lesser Yellowlegs. The bill of the Greater Yellowlegs is slender and longer than the diameter of its head, in contrast to the bill of the Lesser Yellowlegs, which is not significantly longer than its head. In breeding plumage, the bill is solid black, whereas in non-breeding plumage it may be lighter gray at the base. The bill may appear slightly upturned. The Greater Yellowlegs' cryptic plumage is mottled brownish-gray and white, with the breeding plumage brighter and more heavily barred. An important field mark of the bird in flight is its white tail, which is barred at the end. Relative to its size, the legs of the Greater Yellowlegs are shorter than those of the Lesser, with the result that the toes do not project as far behind the tail in flight.

Habitat

Greater Yellowlegs breed in muskeg bogs in the northern boreal forest. Their wintering and migration habitats are more general; they can be found in many fresh and saltwater wetland habitats, including open marshes, mudflats, estuaries, open beaches, lakeshores, and riverbanks. In comparison to Lesser Yellowlegs, Greaters are typically found in more open areas, on larger bodies of water, and on more extensive mudflats.

Behavior

Greater Yellowlegs are less social than many shorebirds, and small flocks form during migration. Outside of the breeding season, most foraging takes place in shallow water. They often feed actively, running after fish or other fast-moving aquatic prey. Greater Yellowlegs swing their heads back and forth with the tips of their bills in the water, stirring up prey, but are less likely to use this foraging technique than are Lesser Yellowlegs. The Greater Yellowlegs bobs the front half of its body up and down, a characteristic behavior of this genus. Greater Yellowlegs are wary, often the first species to sound an alarm when a perceived threat approaches. Greater Yellowlegs are known for their piercing alarm calls that alert all the birds in the area. Their flight call consists of a series of 3 or 4 notes.

Diet

During the breeding season, insects and insect larvae are the primary sources of food. During winter and migration, small fish, crustaceans, snails, and other aquatic animals round out the diet.

Nesting

Due to its low densities and remote nesting areas, the breeding biology of the Greater Yellowlegs is not well studied, and much is unknown about it. They are presumed to be monogamous, and pairs form shortly after they arrive on the breeding grounds. The nest is on the ground, close to the water. It is well concealed in a shallow depression, under a low shrub or next to a moss hummock. The nest is sparsely lined with grass, leaves, lichen, and twigs. Both parents probably help incubate the 4 eggs for 23 days. The young leave the nest soon after hatching and find their own food. The parents appear to tend the young at least until they are capable of fluttering flight, at 25 days, and may stay until they are strong flyers, at 35-40 days. Pairs raise a single brood a season.

Migration Status

A long-distance migrant, Greater Yellowlegs begin moving south from the breeding grounds in late June. During migration, they are found in appropriate habitat from coast to coast. While some stay in Washington through winter, most continue on to the southern US and Central and South America. In spring, they leave South America by March and start heading back to the breeding grounds.

Conservation Status

Hunting led to population declines in the 19th Century, but protection in the form of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 has helped the population recover. Christmas Bird Count data suggest that Greater Yellowlegs are becoming more common in Washington in winter. The Canadian Wildlife Service estimates the population to number 100,000 birds in North America. Throughout their range, Greater Yellowlegs are common and widespread, but their low density, remote breeding grounds, and lack of major stopover or wintering areas make the population difficult to survey. Fortunately, these traits also protect the population from many threats, and their flexibility in migration and wintering habitat will help the population in the face of increased wetland habitat destruction. Protection of this habitat remains important to maintain numbers of this and other shorebird species.

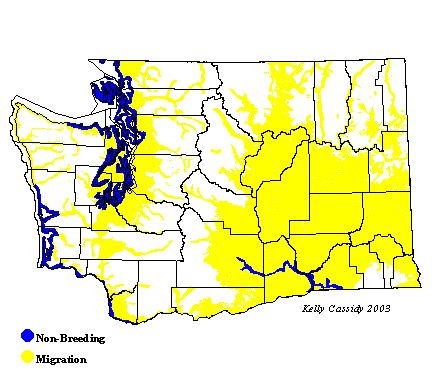

When and Where to Find in Washington

Greater Yellowlegs are common migrants throughout Washington's lowland wetlands. Greatest densities are seen from mid-March through mid-May, and again from late June through October. Some birds remain in Washington through winter, along the coast or in the Puget Trough, and occasionally east of the Cascades along the Columbia River.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | U | U | F | F | F | R | F | F | F | U | U | U |

| Puget Trough | U | U | U | C | F | R | U | C | C | F | F | U |

| North Cascades | U | U | R | U | U | |||||||

| West Cascades | U | F | U | U | F | U | R | |||||

| East Cascades | R | U | R | U | U | U | R | |||||

| Okanogan | U | C | C | R | F | C | U | |||||

| Canadian Rockies | F | U | R | F | F | U | ||||||

| Blue Mountains | R | R | ||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | R | U | F | C | C | R | F | F | C | F | R | R |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria

Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes

Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes Wandering TattlerTringa incana

Wandering TattlerTringa incana Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca

Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca WilletTringa semipalmata

WilletTringa semipalmata Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes

Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda

Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda Little CurlewNumenius minutus

Little CurlewNumenius minutus WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus

WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis

Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus

Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica

Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica

Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa

Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres

Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala

Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala SurfbirdAphriza virgata

SurfbirdAphriza virgata Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris

Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris Red KnotCalidris canutus

Red KnotCalidris canutus SanderlingCalidris alba

SanderlingCalidris alba Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla

Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla Western SandpiperCalidris mauri

Western SandpiperCalidris mauri Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis

Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis Little StintCalidris minuta

Little StintCalidris minuta Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii

Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla

Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis

White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii

Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos

Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata

Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis

Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis DunlinCalidris alpina

DunlinCalidris alpina Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea

Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus

Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis

Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis RuffPhilomachus pugnax

RuffPhilomachus pugnax Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus

Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus

Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus

Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata

Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor

Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus

Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius

Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius